Five Lessons from David Abbott

5 theories for copywriting (with commentary).

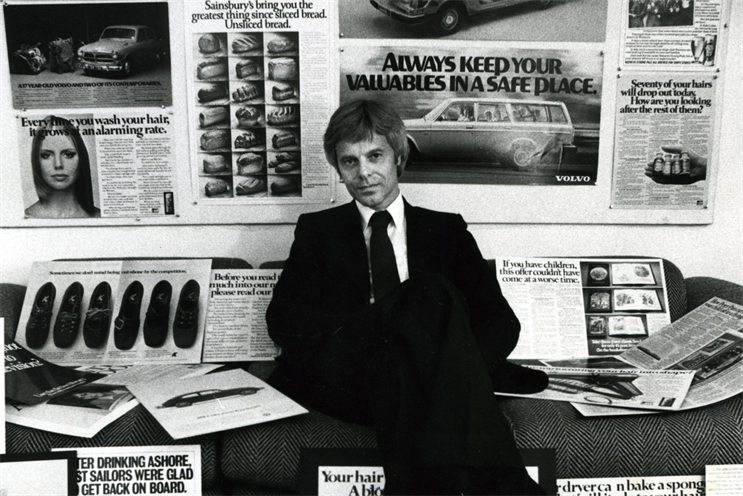

When I fantasized about Madison Avenue, books were all I had to base my daydreams on. They weren’t novels but they had main characters. David Abbott was one of the reoccurring protagonists.

Nowadays, idolizing copywriters from yesteryear is fraught. For good reason, too. Plenty of them were controversial, even by the standards of their time, and they were almost always white, English-speaking, and well-to-do. Not exactly one-to-one role models for anyone who doesn’t fit that description.

David Abbott, however, still has something for everyone.

Who was David Abbott?

David Abbott died in 2014 at the age of 75. By then, he was a famous (without being infamous) copywriter. He started his career writing lines for Kodak in 1960, then hopped from one lily pad to the next, getting bigger and bigger titles the way only someone in the ‘60s could.

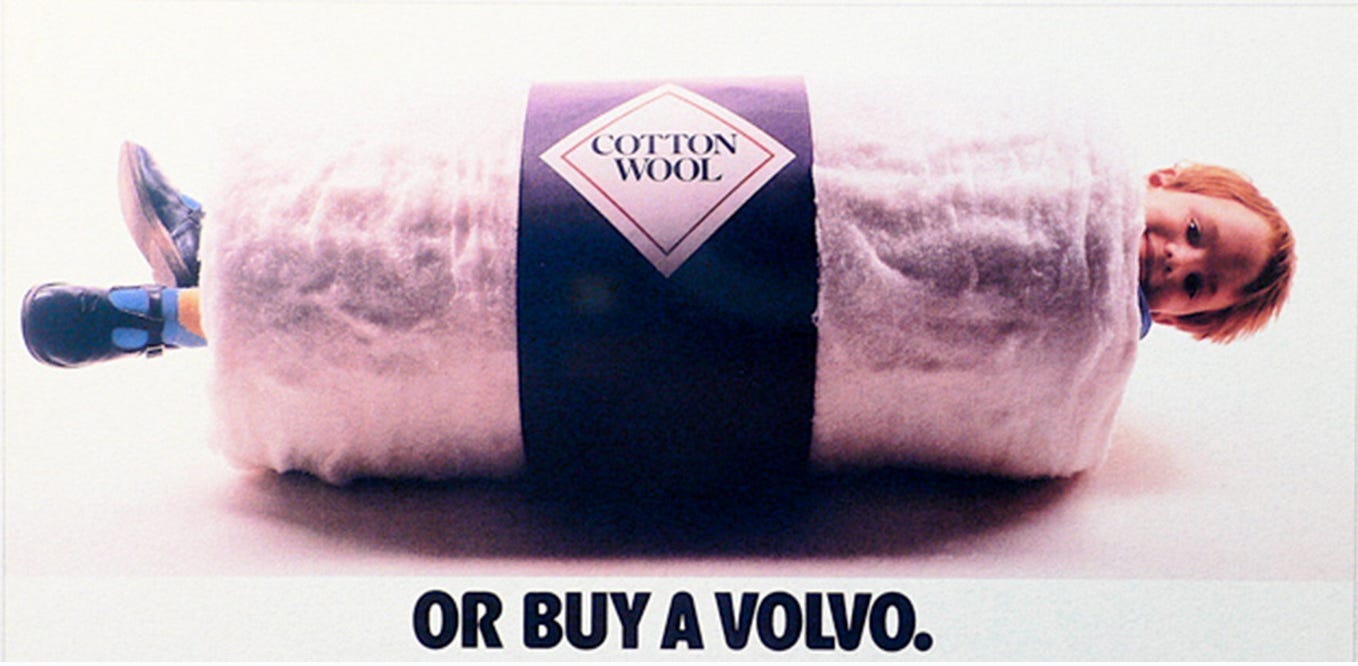

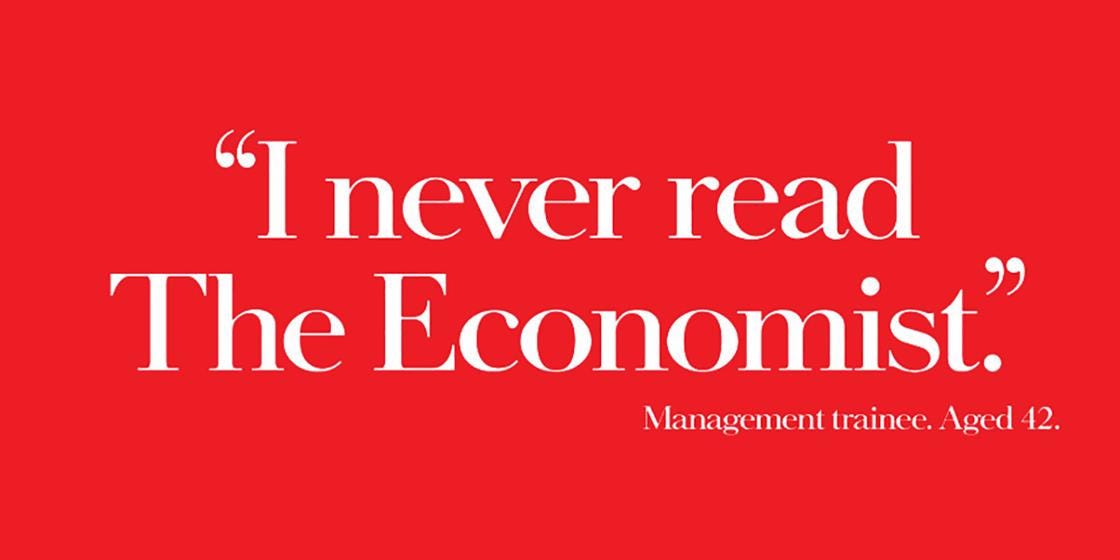

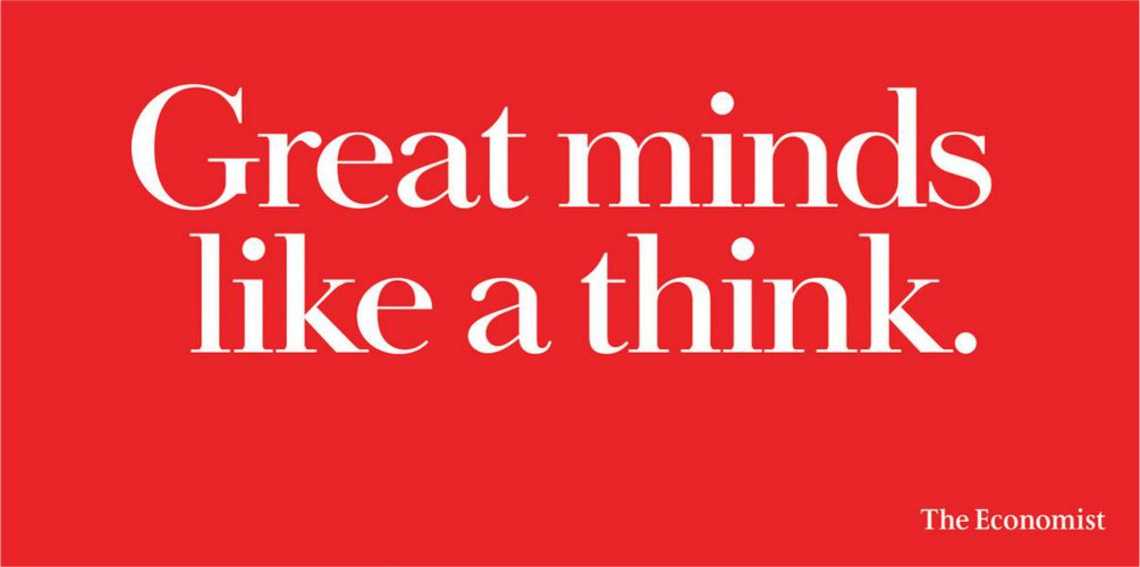

He’s most famous for Volkswagen, Chivas Regal, and—most especially—The Economist. His work on the latter is the canonical “smart copy” that nearly every copywriter and verbal designer works against. “Can we make this copy feel like an Economist ad?” It’s the kind of copywriting that is so good that it became the brand’s tone of voice. Before then, The Economist sold itself with percentage marks and banal promises like everyone else.

Five Theories for Writing

Sometime in the ‘90s, David Abbott sat down at his kitchen table and wrote five theories for copywriting. Here they are in order with some commentary from me in the post-internet age—when copywriting became so much more (and so much less) than what he could have envisioned.

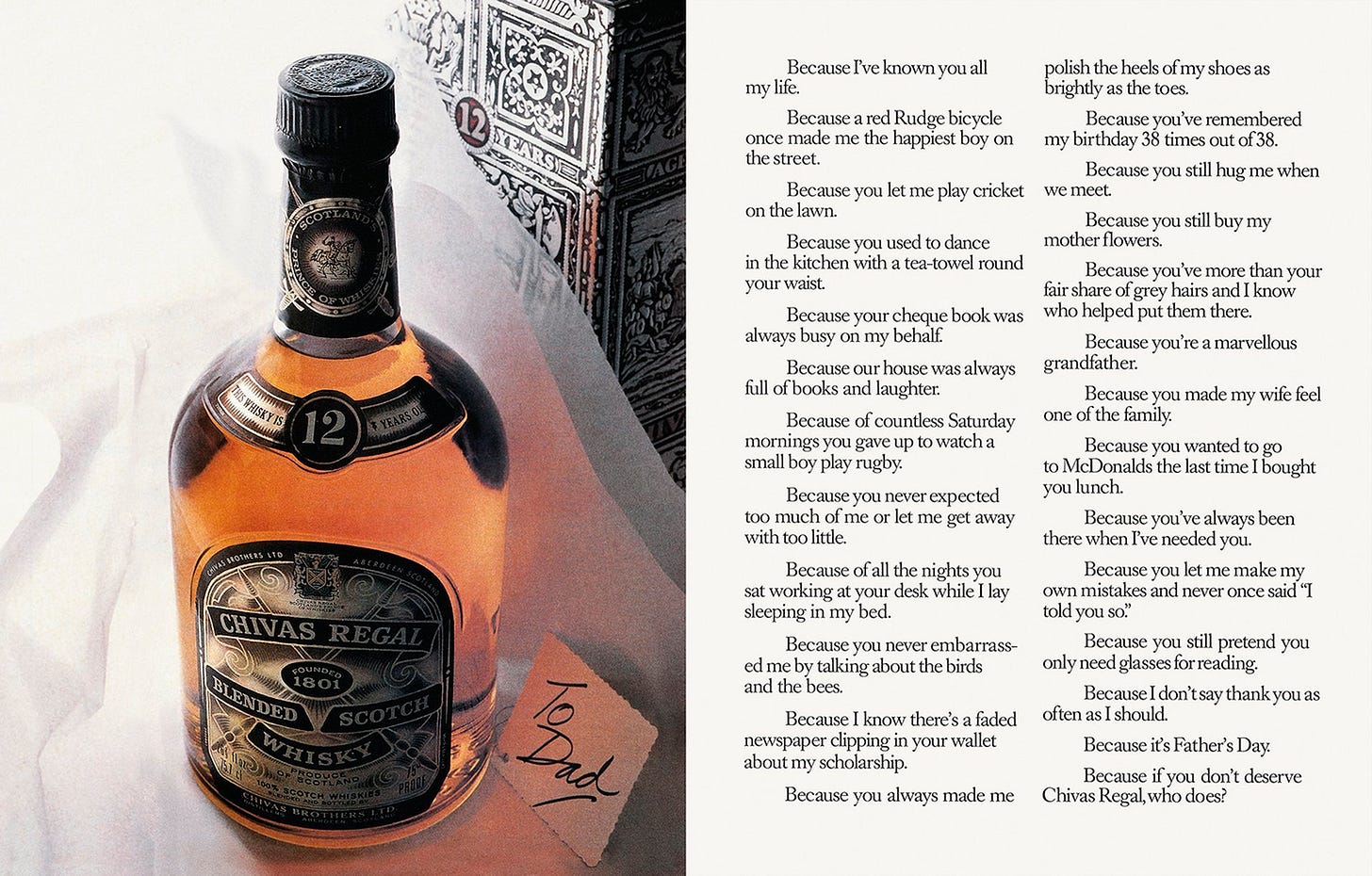

1. Put yourself into your work. Use your life to animate your copy. If something moves you, chances are, it will touch someone else, too.

It was a leap of faith and uphill battle when Abbott was alive. It’s even harder now. You are a massive variable. Anti-matter to most spreadsheets. But the bedrock of this theory still remains—you’re talking to people. They’re just as ineffable and unmapped as you are.

Write with your feelings. It’s the key to triggering other people’s feelings.

Use your personal life as inspiration. It’s real, clear, and inherently visual.

Your memories haven’t been mined by AI. It can feel new in the sea of sameness.

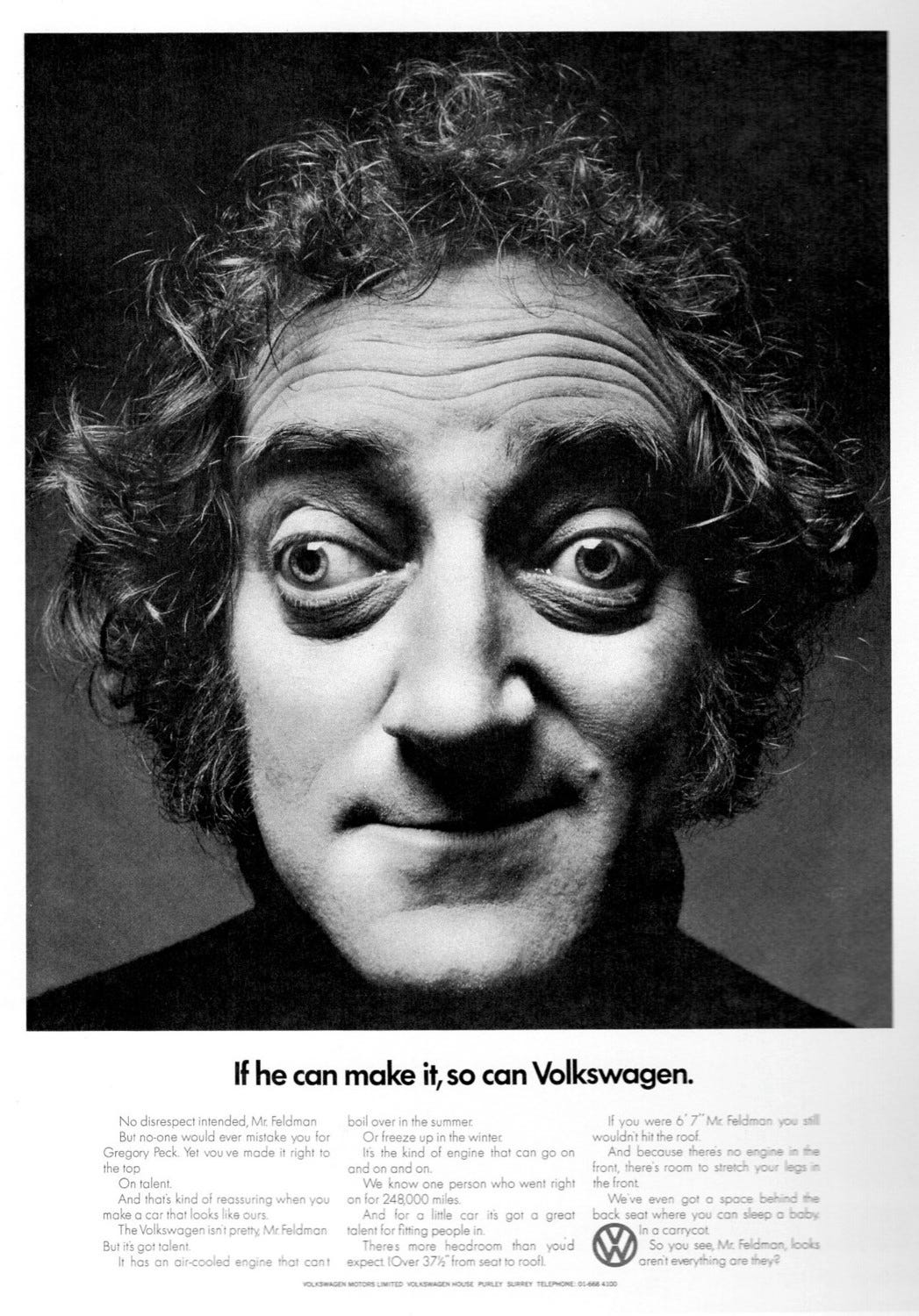

2. Think visually. Ask someone to describe a spiral staircase and they’ll use their hands as well as words. Sometimes the best copy is no copy.

When teaching visual design, I insist that everyone is a writer. We have different sentences to say different things, and sometimes that sentence is a picture. This is the defining reason for verbal designers.

Never write what a visual can say better. It’s usually shorter too.

Your tone of voice will change depending on the visuals. No matter what.

Sometimes the best headline is a brief for the designer. That’s okay.

3. If you believe that facts persuade (as I do), you’d better learn how to write a list so it doesn’t read like a list.

Once upon a time, lists were how we wrote for brands. A lot of the “greats,” like David Ogilvy, wrote almost exclusively in lists. It makes sense. Lists have a natural progression, cadence, and easy-readability. So what can we learn from them?

Facts sing in a story, structure, or rhythm. Lists are one method.

Facts and statistics are not the same thing. Relatability and context is king.

Facts without insights aren’t facts at all—they’re just non-sequiturs.

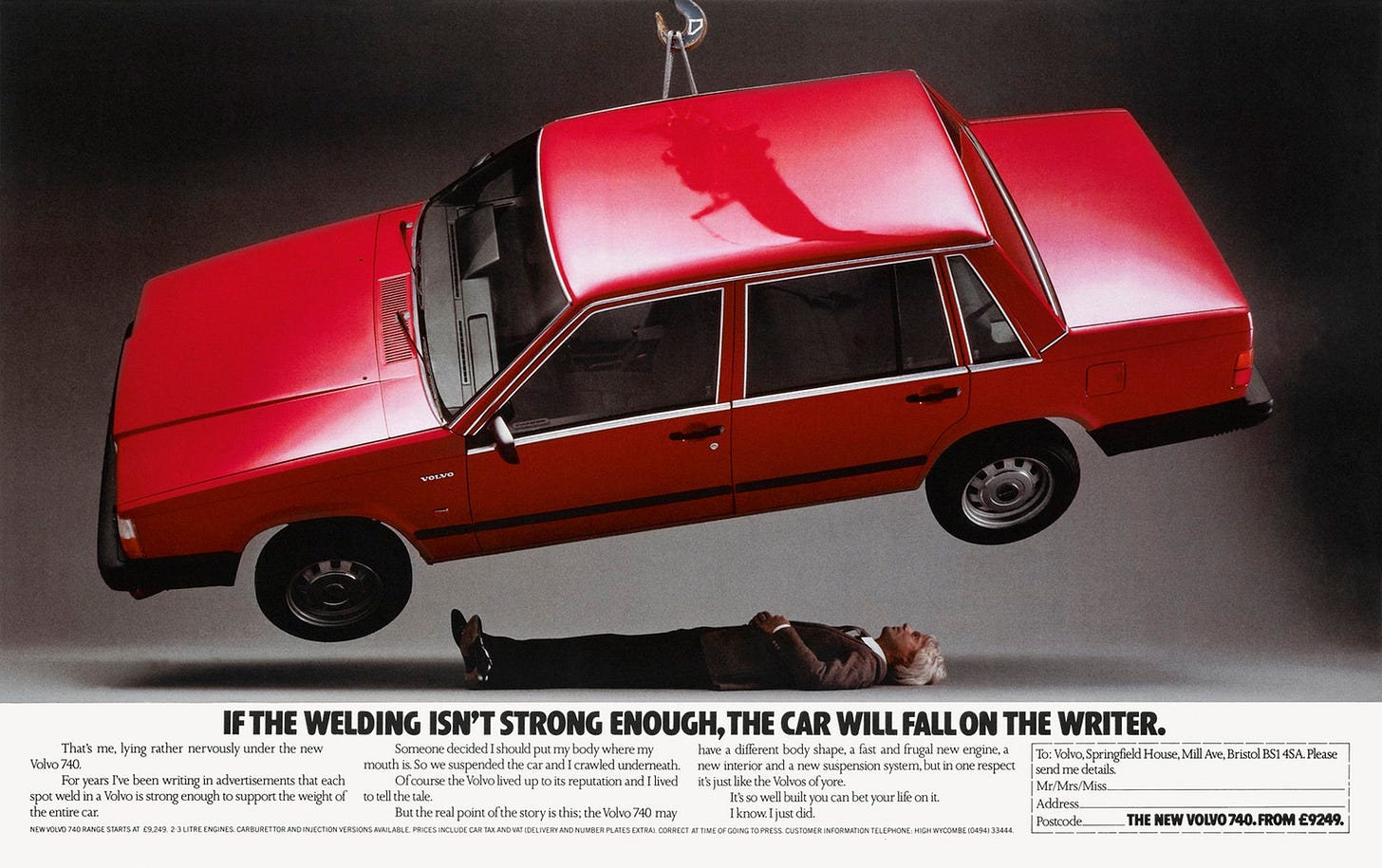

4. Confession is good for the soul and for copy. Bill Bernbach used to say, “a small admission gains a large acceptance”. I still think he was right.

One of the things that’s interesting about copywriting from this era is how self-referential it is. Abbott breaks the fourth wall a lot. It’s not self-aware like ads today. There’s no irony or wink at the audience. It’s more like a workman’s transparency.

Fewer ads that know they’re ads. Self-awareness without confession is a stunt.

Saying the truth, even if the truth ain’t pretty, can build trust.

Audiences know what ads sound like, but most don’t know how they’re made.

5. Don’t be boring.

Some might argue this idea is so basic it’s not worth mentioning, and yet most brands are boring—especially their verbal identity. Speaking from experience, I’ve never heard a mentor caution this outside of a classroom. Probably because it doesn’t have objective indicators. How do you know something is boring? The unsatisfying answer is: when it feels boring. In our modern age, “a feeling” is the least defensible reason for anything, unless you have a high degree of trust with the client.

Trust your gut. If what excites you, excites others, the inverse is also true.

Boring subject matter doesn’t automatically mean boring verbals.

If you don’t have a lot of trust with clients, boring will be hard to kill.

Last word with The Economist

The legendary campaign lives up to Abbott’s last theory. To quote the writer himself, “What is potentially a banal positioning (“read this and be successful”) is made acceptable and convincing by wit and charm.”

Anything can be interesting if said in an interesting way.

“Directness has its place in advertising but so does subtlety and obliqueness. Things you can’t say literally can often be said laterally.”

Maybe the art of good copywriting is to not resemble copywriting.

Until next time,

Clayton.